I intended for this post to be about some cool ass joggers and men’s pajamas pants I discovered during the pandemic, but my photo taking abilities were thwarted by the ice encrusted snow. In the meantime, I’ve been a caregiver for my aunt who many of you met at the shop. For those who missed the posts on Facebook, Debbie suffered a devastating stroke on Thanksgiving and was hospitalized for over a month. She has zero sensation on her dominant side and needs significant care. She’s staring down the barrel of long term and most likely chronic illness.

Dealing with the stroke aftereffects as well as my own health struggles reminded me of a writing prompt, and I want to introduce those pieces to the blog. This particular assignment came from a Coursera writing class and focuses on a second person piece about a common event, such as a piano recital, visiting family, or even a doctor’s visit.

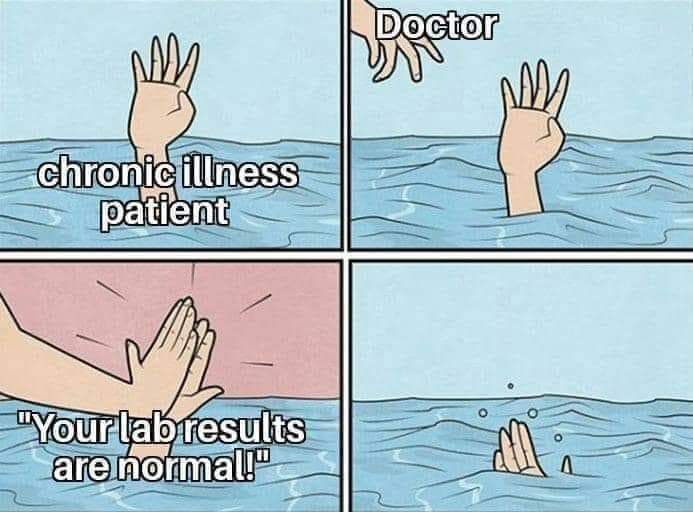

I cannot ever recall writing anything in second person like this. Aside from this blog, I barely write first person pieces. However, the idea and emotion powering the story centers on sick bodies and how we are frequently at the mercy of our providers, whether they are right or not. We didn’t learn the extent of my aunt’s stroke until they were ready to discharge her despite repeated attempts to follow up, and it took me three years for anyone to acknowledge I had a thyroid problem.

If you get nothing else from this, it must be: Be your own advocate and fight like hell to get the treatment you deserve.

Otherwise, this is my first semi-autobiographical piece written in a second person format, and I’m putting aside insecurity to publish it. I hope you enjoy it. I love sharing ideas and writing, so I’m here for feedback or your own posts. Lastly, if you get a chance, I highly recommend the entire Wesleyan course series. The videos and information are excellent, and the writing assignments are challenging. Stay warm!

-Erica

You stare at yourself in the bathroom mirror, agonizing over whether to apply makeup. Will they take you more seriously if they can see the dark circles under your eyes and the blotches dotting your cheeks? Will the swipe of gunmetal eyeliner undermine how tired you are, forever struggling between what you want to do and what you can?

The image of unforgiving florescent lights shining their sterile beams on your imperfections pricks at your pride until you squirt out the tinted liquid on the back of your hand. You apply it lightly to ensure you don’t seem capable of much effort. Remember: looking sick is as important as being sick.

Last night you assembled a thorough account of your medical history—lab results with dates, itemized lists of medications and side effects, and a timeline of how your body started to betray you. Your hands shake as you steady your breath. If you cannot quell your racing heart, the blood pressure readings skyrocket and become something else the doctor would rather treat than your actual illness. You’re not allowed to be nervous.

As you drive to the plain brick building, you play your favorite songs on low to comfort you while you rehearse and rehearse, selecting each word for its impact and culling others to keep their attention. Doctors only hear so much, and it’s imperative to choose the right phrases to communicate your symptoms.

When the bone-deep fatigue started and you had this growing feeling something was wrong, your appointments were filled with buoyancy. You would narrate your symptoms with the optimism born from believing doctors not only can help but want to do so. They are the wardens of the wisdom you need to heal your body. They know more than you, and for the price of your copay, they impart their knowledge.

Take these pills, and in a week, the sore throat will be gone. Wear this cast for a while, and the fracture will heal. The answer was always the same: You will get better. And it was always true. You did get better, which is why you feel dejected and depressed. This time you keep getting worse.

By now, you’re jaded and exhausted, not only from being sick but also from the fight, from the battle of wills every time you demand to be heard. You’ve realized doctors are not always benevolent healers doling out personalized advice but rather combative gatekeepers convinced they know more about your body and what it needs than you do. Your lived-in experience is nothing compared to their textbooks and case studies and common denominators of treatment. You can’t be trusted.

Simply walking through the glass doors fills you with dread. You sign the swirl of your name with the upbeat receptionist, and your heart pounds, radiating anxiety throughout your body like a beacon. You sit in a cheap, hardened chair and check and recheck your packet of information.

Midday soaps play at low volume on the television while you open a game on your phone, letting the repetitious sliding movements of your fingers soothe you. The nurse barks your name from across the waiting room, and you fumble with your papers, nearly splattering them across the thin industrial carpet. She is about to call you again, so you pop up and wave like she’s taking attendance in elementary school.

She leads you toward a room with a scale and motions for you to step up. Weight is incredibly important with illness. It’s always the first thing they consider when diagnosing you. The nurses catalog it constantly, often commenting on the number and how it changed from last time, regardless of whether you prefer not to know.

The red digits flash on the thin black screen, and your heart sinks as you realize you gained. Next is your blood pressure, which is a little above normal, and the nurse sympathetically asks if you’re nervous. You force a smile and nod because the nurse wants a “yes” or “no.” She doesn’t want the long answer of how doctor’s appointments impact you.

She guides you to one of the many identical exam rooms with more uncomfortable chairs. Bland paint is splashed across the wall, and a non-descript landscape in a large gilded frame hangs crookedly across from you. A white noise machine gurgles like a brook, urging you to relax and have faith in the power of this room.

The nurse copies your symptoms into the computer and genuinely seems interested. The nurses always are, and they may be your single respite of compassion throughout this process. This entire act—the dialogue between you and her where you outline why you are there and she with equal care transcribes the information with appropriately considerate expressions—is meaningless. The doctor never reads all of her notes. He gives them a cursory glance before jumping to his own conclusions.

“The doctor will be with you shortly,” she says. Sometimes they are while other times you wait over an hour, alone in the room with the gurgling brook and the painting of a tree in autumn. Finally, the doctor performs the classic knock-and-enter, which manages to both prepare and surprise you.

“Good afternoon,” he says without looking at you. “I see you’re here because you think you have a thyroid problem.” Notice how he comments with “you think.” He wants to cripple your confidence, start the appointment with you on the defensive and forced to prove yourself to him. This is why you prepared, and you reach for the papers like they are a weapon. What seemed excessive becomes your constructed proof, an ironclad argument for why you know you are sick and why you need a different treatment.

You smooth out the soft folds of your skirt, pausing to breathe, and respond “I know I have a thyroid problem. Here’s a more comprehensive medical history along with the corresponding blood work and notations on the medications I’ve tried and to what degree of success they had.” You annunciate each word with a strong sense of finality. You don’t want to allow him to wiggle his way out of acknowledging what you see.

He sighs and looks at his watch, and you realize he will give them the same perfunctory attention as your chart, taking in the highlights without absorbing them. “Well, these problems could be accounted for because you’re overweight.” He looks at you and judges while his own pot belly gorges over his belt and his swollen fingers trace the words in the file.

For the next five minutes, the entire time he’s allotted to examine you, you’ll spar. He’ll tell you it could be one problem while you reference the file he never read and demonstrate why it isn’t. He’ll suggest a new combination of medication, and you’ll explain it isn’t new and list the horrendous side effects. “Are you sure you can’t handle the diarrhea? If you take a bunch of iron tablets, they should counteract the Tricor to improve your triglyceride levels.”

He’s escalated now, forcing you to talk about the more embarrassing aspects of having a body, especially a sick body. You want to swear, to scream and maybe slap him, but above all, as a sick woman, you must be calm. If you let him see the anger raging behind your eyes or the way your body wants to heave with sobs, he will write you off more than he already has. You’ll be hysteric. Keeping your composure, you explain how you cannot tolerate nearly shitting yourself every day at work so he can prescribe a medication you found unbearable.

When you’ve refused his suggestions and he’s refused to listen, you reach the impasse. He cannot diagnosis you further without new labs, but he’s angry you challenged him and takes another stab. “Your TSH numbers on the previous work are normal despite the presence of thyroid antibodies, so your thyroid isn’t as bad as you think. I doubt the numbers will change.” It’s the double punch, the one-two. He references the lab work to undercut your problem and demoralizes your experiences. Doctors always know your body better than you.

He prints out paperwork for you to take to the lab to exact more blood, but you know what the results will be. Something other than the illness causes your symptoms. It’s always your fault. You don’t exercise enough. You don’t eat the right kind of foods. You don’t sleep enough at night. You don’t take the right supplements. You don’t understand how your own body works.

Only the doctor knows, and only the doctor can provide you with treatment. You can’t be trusted to give a proper account of what it feels like to live as you, and so you keep going to doctor after doctor, each time hoping one will listen, that one will recognize it’s not your weight or your age or your gender or your habits. It’s your body. You live in a sick body, and this is your life.

Leave a Reply